James Graham on Anarchy

Thu 21 May 2015 |

Our Plays, The Bigger Picture

“Get pissed, destroy” scream the Sex Pistols in the closing notes of Anarchy in the UK, their first single release.

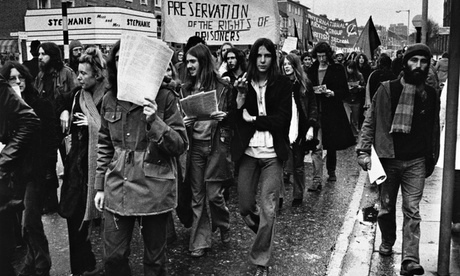

The young London revolutionaries hanging out in the bookshops of Camden and the communes of Notting Hill might not have recognised themselves in that sentiment. Their movement was not about mindless rioting; theirs was an intellectual one, born out of universities and coffee houses. Their obsessions were social justice, freedom, and the rejection of a class-based, unrepresentative establishment in power.

You might not have heard of the Angry Brigade. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard of them when I eventually heard of them. During their campaign, between 1970-71, they sent communiqués to newspapers and the authorities, made using a children’s printing set.

“We are no mercenaries. We attack property not people,” they wrote in communiqué 5. And in communiqué 7: “The politicians, the leaders, the rich, the big bosses, are in command… THEY control. WE, THE PEOPLE, SUFFER…” And in Communiqué 9, they wrote: “The AB is the man or woman sitting next to you. They have guns in their pockets and anger in their minds. We are getting closer.”

A lot is still contested and unknown. Some define them as the first home-grown mainland terror cell – perhaps surprising, today, given they were white, university-educated men and women in their 20s. An urban guerrilla outfit who set off – or were linked to a network that set off – 25 explosions around London, at the homes of cabinet ministers, senior judges, police commissioners. They detonated devices in fashion boutiques and monuments to capitalism, such as the Post Office tower. When they were eventually caught – living together in a Stoke Newington flat, in what the tabloids described as a “bomb factory” – alleged perpetrators John Barker, Anna Mendelssohn, Hilary Creek and Jim Greenfield were sentenced to 10 years, following the longest criminal trial in English history. So long, in fact, that in a classic example of the idiosyncrasy of the very British establishment under attack, the judge brought in a cake for one of the defendants on their birthday.

And yet, silence has defined them since their release. Anna Mendelssohn became Grace Lake. Her family and friends tell me of her relocation to Cambridge, as a mature student exploring her gifts as a poet and painter. I don’t know the whereabouts of Jim Greenfield, the son of a Widnes lorry driver. Hilary Creek is thought to be in France, possibly Italy. John Barker, a novelist, spoke eloquently of his undiminished fury to the Guardian earlier in the year. “Looking back, the kind of things the Angry Brigade did would be far more relevant now,” he said. “But I feel angrier than I ever felt then. The way in which the crisis of 2007 got flipped, so that suddenly it’s not bankers but people living on welfare who are the problem, was extraordinary. These are horrible times.”

It’s that financial crisis that surely led to the activism, such as it is, we observe around us today. It pulled open the wizard’s curtain, caused a glitch in the matrix that made us blink. Prior to that, in a world post-Thatcher and “Third Way” Blair, there was one assumed way to organise the world. This is being questioned again. And if we are to believe in the politicisation of normal men and women, young and old, around the dinner tables and bar stools of Scotland, then something has happened. Something has changed.

“Blow it up or burn it down” was the cry of the Angry Brigade. I’m not advocating that. But as a politically engaged young person it was always disconcerting to be continually told how young people were not politically engaged. Our tools are different – and I’m not always convinced by their effectiveness. Where once there were trade unions there are now Facebook groups. Where once we marched, now we sign petitions. But if anarchy is defined (as it was intended) as the belief in progress and change when progress and change become necessary, then through the mere asking of the question “Why does it have to be this way – just because it always was?” perhaps the reigniting of a little anarchy in all of us is a healthy, exciting and, above all, quite a surprising thing.

This article was originally published in The Guardian 20 September 2014. Read it in full here.