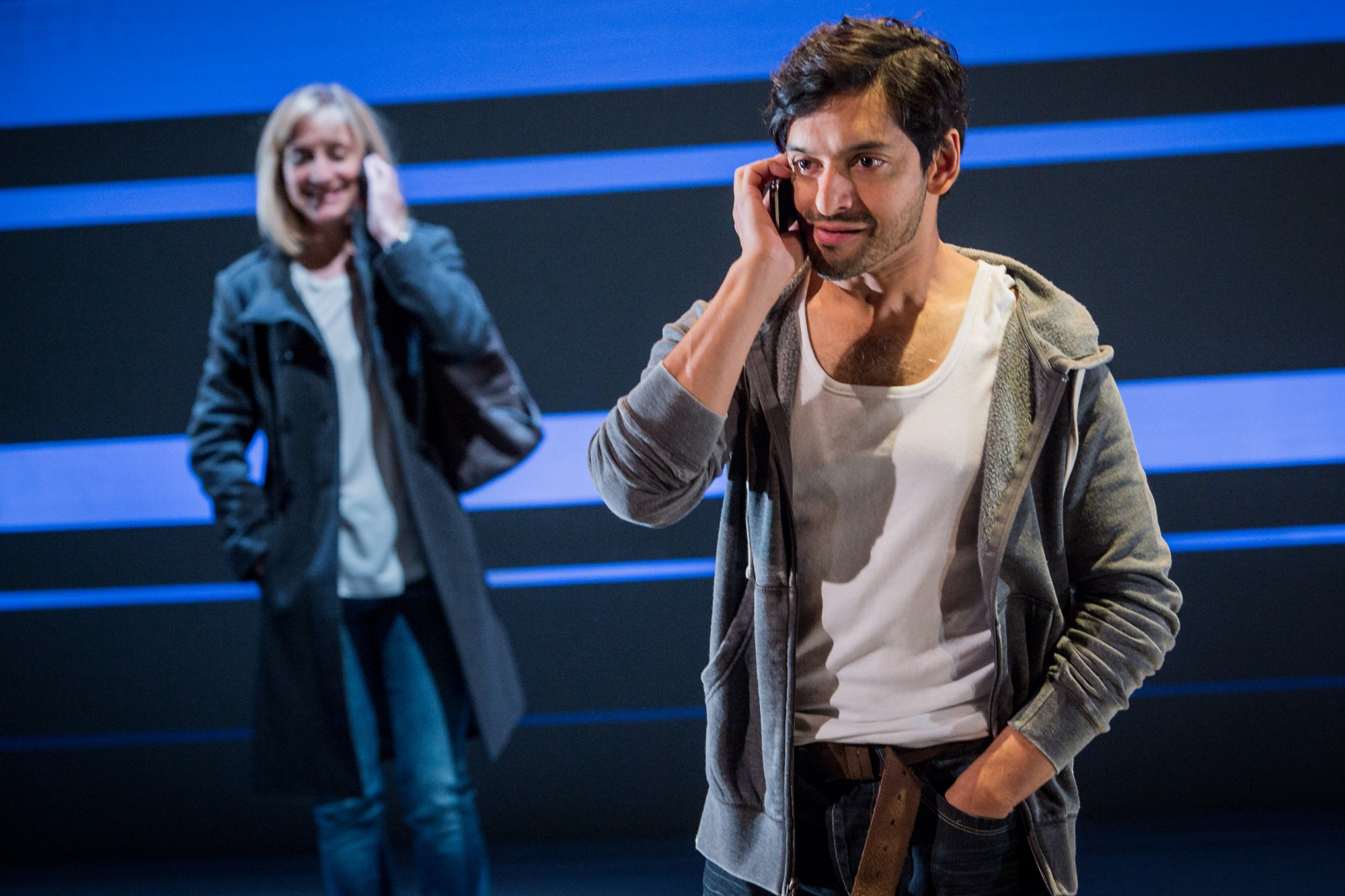

CIPHERS and Real Spies Throughout History

Tue 21 Jan 2014 |

Our Plays

14th January, 2014

We wanted to learn more about real life spies and whilst Dawn King’s new play Ciphers was here at the Bush in January 2014 looked in to some of the more memorable people going undercover.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

(1915/1918 – 1953)

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were American Communists who were executed for passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union. They met in the Young Communist League in 1936 where he was a leader and had two sons. Julius was recruited by the KGB in 1942 and was regarded as one of their top spies. He passed classified reports from Emerson Radio, including a fuse design which was later used to shoot down a U-2 in 1960. Despite others being arrested and tried under similar charges receiving only prison sentences, and notwithstanding the undetermined extent of Ethel’s involvement, the couple were sentenced to death by electric chair.

Aldrich Ames

(b.1941)

Ames is a former CIA Counter-intelligence Officer who was convicted of spying for the Soviet Union in 1994. On his first assignment as a case officer, he was stationed in Ankara, Turkey, where his job was to target Soviet intelligence officers for recruitment. Due to financial problems in his personal life as a result of alcohol abuse and high spending, Ames began spying for the Soviet Union in 1985, when he walked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington to offer secrets for money.

Ames was assigned to the CIA’s European office where he had direct access to the identities of CIA operatives in the KGB and Soviet Military. The information he supplied to the Soviets lead to the compromise of at least 100 CIA agents and to the execution of at least 10. He ultimately gave the USSR the names of every CIA operative working in their country; for this they paid him 4.6 million dollars. Ames used the money to live well beyond his means as a CIA agent, buying jewellery, cars, and a $500,000 house. He is now serving his sentence in a high security penitentiary in Pennsylvania.

Giacomo Casanova

(1725 – 1798)

Casanova, born in Venice, is most well known for his womanizing and his book The Story of My Life which gives the best account of life in the eighteenth century that we have. With the financial support of many of his mother’s patrons he was able to go to school to receive a very good education. This enabled him to become a lawyer. Over many years his romantic affairs with women in power made him a very powerful man. He gained and lost riches at a rapid rate (in one case he lost the equivalent of over 1 million Euros in one night).

Between the years of 1774 and 1782, he worked as a spy for the Venetian Inquisitors of State. It is not known what his role involved as his famous diary ended the year he began his work. In 1782 he was exiled from Venice for spreading libel against one of the City patricians.

Klaus Fuchs

(1911 – 1988)

Fuchs was a German-born theoretical physicist who worked in Los Alamos on the atom bomb project. He was responsible for many significant theoretical calculations relating to the first fission weapons and early models of the hydrogen bomb. Whilst attending university in Germany, Fuchs became involved with the Communist Party of Germany. After a run-in with the newly installed Nazi government, he fled to England where he earned his PhD in physics. For a short time he worked on the British atomic bomb project.

It was while he was working for the British that he began to give information to the Soviets. He reasoned that they had the right to know what the British and the Americans were developing. In 1943 he was transferred to the United States to assist on the Manhattan project. From 1944 he worked in New Mexico at Los Alamos.

For two years he gave his KGB contacts theoretical plans for building a hydrogen bomb. He also provided key data on the production of uranium 235, allowing the Soviets to determine the number of bombs possessed by the United States. On his return to the United Kingdom in 1946, he was interrogated as a result of the cracking of some Soviet ciphers. He was tried and sentenced to fourteen years in prison, the maximum term under British law for passing military secrets to a friendly nation. He was released after nine years and immediately moved to Germany where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Major John André

(1750 – 1780)

John Andre was a British officer hanged as a spy during the American Revolutionary war. At the age of 20 he joined the British Army and moved to North America to join the occupying forces. He was a great favourite in society, both in Philadelphia and New York during their occupation by the British Army.

During his nearly nine months in Philadelphia, André occupied Benjamin Franklin’s house, where it is said he took items from Franklin’s home when the British left Philadelphia.

In 1779, he became adjutant-general of the British Army with the rank of Major. In April, he was placed in charge of the British Secret Intelligence. By the next year (1780) he had begun to plot with American General Benedict Arnold, who commanded West Point, and had agreed to surrender it to the British for £20,000 — a move that would enable the British to cut New England off from the rest of the rebellious colonies.

Using common clothes and a false passport, Andre travelled toward New York with documents supplied by Arnold. He was stopped by three men at gunpoint. In the conversation that followed in which both parties were confused over the allegiance of the others, Andre admitted he was British. The three men searched him and found the papers he was hiding. He was put on trial before a board of senior officers. On September 29, 1780, the board found Andre guilty of being behind American lines “under a feigned name and in a disguised habit”, and that:

“Major Andre, Adjutant-General to the British army, ought to be considered as a Spy from the enemy, and that agreeable to the law and usage of nations, it is their opinion, he ought to suffer death.”

He was hanged as a spy at Tappan on October 2, 1780.

Nathan Hale

(1755 – 1776)

Nathan Hale was a captain in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He is widely considered to be America’s first spy after he volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission, but was caught by the British. He is best remembered for his speech before his hanging, in which he said: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country”.

With the break-out of the Revolutionary war in 1775, Hale – a teacher who graduated from Yale with 1st class honours – immediately joined a Connecticut militia, becoming a first Sergeant. During the Battle of Long Island, Hale volunteered to go behind enemy lines to monitor the movements of the British. He disguised himself as a Dutch teacher and made his way to New York. He was captured in a tavern after he was tricked into betraying himself as a patriot. He was apprehended near Flushing Bay in Queens.

He was reportedly questioned and found with physical evidence. According to the traditions at the time, he was found guilty of being an illegal combatant – a crime carrying the death penalty. He was taken to what is now 66th Street and Third Avenue and hanged. He was 21 years old. A British officer wrote this of Hale at the execution:

“He behaved with great composure and resolution, saying he thought it the duty of every good Officer, to obey any orders given him by his Commander-in-Chief; and desired the Spectators to be at all times prepared to meet death in whatever shape it might appear.”

Source: Excerpts taken from Out of Joint’s Ciphers Education Pack. Information compiled by Gemma Richardson & Cameron Reynolds from Queen Elizabeths Community College, Crediton; with help from Malaika Kegode, Box Office Assistant at the Exeter Northcott Theatre. Final edit by Lee Pritchard, Out of Joint work experience, 2013.